Both the government of Mozambique and the mining companies Rio Tinto and Riversdale Mining Ltd. knew that the resettlement of 736 families to the remote area of Mualadzi would severely deteriorate their living conditions, long before they moved the communities.

This goes against Article 86 of Mozambique’s constitution and the national Mining Law, which state that people cannot be resettled if it changes their living standards for the worse, and international guidelines defined by the World Bank and enforced by the International Finance Corporation, IFC, stating that involuntary resettlement “should be conceived as an opportunity for improving the livelihoods of the affected people and undertaken accordingly.”

Danwatch has obtained the Benga Resettlement Action Plan (RAP) that guided the process of moving local communities away from the Benga mine concession area in Tete, Mozambique. It clearly describes Mualadzi as an area lacking sufficient water resources:

“The surface water resources are poorly developed in the area with no perennial water course running within or nearby the development area. The existing seasonal streams are highly dependent on the wet season for their flow pattern and therefore cannot be considered a continuous water source,” the RAP states.

Knowing the poor water conditions in the area, the mining company Riversdale Mining Ltd. and the Tete provincial government chose Mualadzi as the new home for the communities, and moved them to the remote site before further investigation into the water availability had been concluded and long before a solution was found, the RAP shows.

In 2010 Riversdale Mining Ltd. began the resettlement process by moving people and livestock 43 kilometres away from their villages in order to make way for their Benga coal-mining project. Shortly after, Riversdale Mining was taken over by the third largest mining

company in the world, Anglo-Australian Rio Tinto, while British-Indian Tata Steel kept its 35 percent stake in the mine. Along with the majority ownership came the responsibility to finalise the resettlement of all affected communities.

In 2011 Rio Tinto carried out the largest phase of the resettlement by moving 358 families to Mualadzi. Because water resources were poorly developed in the area, a technical team was to design and install water systems that could make up for the lack of natural water in the area. But according to the RAP from 2009, Riversdale and the government knowingly moved people to Mualadzi before a solution had been found.

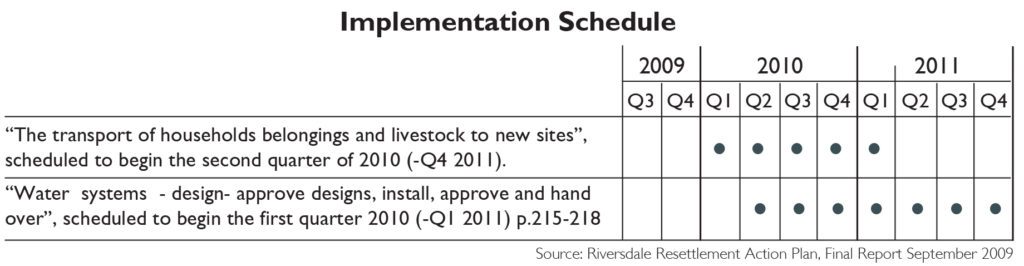

The transportation of families and livestock was scheduled to take place while the technical team was still researching the water conditions in the area – and a year before a solution would be put in place – according to the implementation schedule included in the plan: The RAP further shows that if no sustainable solution to the water problem was found, the company and the government would need to find an alternative resettlement site.

“The water availability of the Mualadzi site will be confirmed during the implementation phase, but should this prove to be insufficient then a further process of site identification will be undertaken.”

When Rio Tinto took over the process of resettlement, the company continued along the lines set out by Riversdale Mining and moved more than 300 families to Mualadzi. To make up for the water shortage, Rio Tinto drove water tanks to the resettlement site where people could fill their water containers. But the water supply was unreliable and the community would sometimes wait in days for the next delivery, according to a report from Human Rights Watch, which conducted a large survey in the area in 2013.

Today, field research from Danwatch shows that people still deal with the aftereffect of the resettlement to Mualadzi. They have lost their livelihoods, and years of food and water scarcity has pushed the community to the verge of desperation. Several sources describe how water shortage poses an immediate challenge. One of them is 37-year-old Josefina Torres:

“We don’t have enough water, so we need to wash where the cows are drinking,” Torres says. For the mother of five, the question of how to get enough food and water for her children is a daily concern. She and her husband are trying hard to make ends meet in their new life:

“There is no work for us here. We used to make bricks and break stones for construction, but here we don’t know what to do. We are hungry, and sometimes we only have one meal per day,” she explains.

The family was given a small piece of land when they came to Mualadzi, but the lack of water makes it nearly impossible to grow anything in the soil, described in the RAP as “rocky” and “shallow,” so they currently live off a small store of maize from last year – far from enough to feed the family of seven, Torres says.

Josefina Torres, 37, and her family has been resettled to the Mualdazi area, because the area they used to live in was expropriated for coal mining. But the house they were given as compensation was too small. Her children, husband and a friend of the family have begun to make their own bricks to build an addition to the house. Photo: Jesper Kirkbak

The move to Mualadzi meant a drastic change for the affected communities that used to live in close proximity to the city, where unlimited access to the water running in the Zambezi and Revuboè rivers allowed them to cultivate their land all year round.

The Resettlement Action Plan shows that Riversdale Mining foresaw the challenges awaiting the families when they listed water availability as one of the anticipated losses connected to the move to Mualadzi. The plan describes how “the majority” of the affected families in Capanga rely on drinking water from the Revuboè river and other streams, especially during the dry season; it also describes how the families used to have access to community wells and how some had access to piped water outside their homes.

“These water sources will no longer be accessible to the affected households when they leave the EZ (exclusion zone, red.) and the Capanga area,” the plan states (p.116, list of key losses p.123). Paradoxically the choice of Mualadzi goes against Riversdale’s own criteria for host area selection, including “adequate and suitable existing or potential water supplies, occurrence of sufficient soils suitable for agriculture and easy access to the site.”

The criteria, however, are not prioritised and Riversdale make clear reservations,

stating that

“While the set of suggested criteria was applied (in the site selection, red.) it was recognised that: it would be unlikely that all the criteria would be met for any particular case. Thus, potential host areas which satisfied the greatest number of critical criteria were selected,” the plan reads.

Despite the fact that mining-induced resettlements have been going on for years in Mozambique, no laws existed to regulate the resettlement processes itself until 2012 when the Resettlement Decree was issued, says Dr. Jose Macuane from the Eduardo Mondlane University in Maputo, who researches political economy and natural resources. But where specific legislation on resettlements falls short, other laws apply:

“This is essentially a rights issue. According to national law, companies should restore or improve the living conditions for the affected people, and the government should make sure that it happens, but the government in Mozambique hasn’t been effective in this,” he says.

According to the country’s Land Law legislation that defines the rights to land use and rules of compensation, individual citizens, communities or other entities who occupy land in good faith and according to customary practices have the right to unlimited use and benefit from that land, a right which may only be taken away by fair compensation. Still, the conditions in Mualadzi have not caused the companies or the government to find an alternative, more hospitable location for the families.

Before Mualadzi was chosen as the resettlement site, the communities in Capanga were wary about the location. They questioned whether the soil was suited for agriculture and they were concerned about the distance to Tete and the Moatize markets, the Resettlement Action Plan shows.

According to the plan, the community’s concerns about the resettlement site were put forward on at least three different occasions. At a general meeting in February 2009 the community expressed concern about the location and conditions present in Mualadzi. In July 2009 they stressed the need for a location with sufficient water resources that would allow them to produce crops all year round, like they were used to. Similar points were made during focus group discussions in the same period.

The plan summarises the conditions put forward by the communities, which contains demands like a location near a riverbank, good soils for fields (machambas) and grazing, access to Zambezi and Revuboè islands and houses and other structures – structures such as cattle pens and chicken coops must remain close to the main residential structure for better control of the livestock.

Contrary to the community’s wishes and despite the questionable conditions in the area, the government and Riversdale selected Mualadzi as a suitable resettlement site, while acknowledging the “lack of consensus.” To date, a permanent solution to the water issue has not been found, and the community in Mualadzi still relies on the current owners of the Benga mine, ICVL and Tata Steel, for their water supply.

Danwatch has contacted all the implicated mining companies and presented them with our findings. Rio Tinto, which moved the largest group of people to Mualadzi, has declined to say why the company did not put an alternative plan into play when faced with the realities in Mualadzi.

The right to an adequate standard of living, including the right to water, is protected by article 11 in the UN International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). In a business setting, it means that companies should take “reasonable steps to ensure that their operations do not adversely impact the availability, accessibility and quality of clean water, both in the short and long term,” according to the consultancy

Global CSR in a guidebook to business.

Rio Tinto, known for its strong CSR profile, also subscribes to the standards outlined in the IFC Handbook on Preparing a Resettlement Action Plan, which serves as the only comprehensive corporate guide dealing explicitly with the complex issue of involuntary resettlement. In a written statement to Danwatch from 13 August 2015, Rio Tinto

states:

“We take our responsibilities to local communities seriously and to the point of transfer, our activities worked to meet internal and international standards. This is difficult and complex work and its success cannot be judged after 12 months, two or even five years. In particular, livelihood restoration for households takes time given the multi-year nature of this process.”

Danwatch have asked Rio Tinto how the company’s standards comply with its involvement in the resettlement of hundreds of families, but they have declined to answer the question. The responsibility lies with the government and the current owner ICVL, they say, stressing that “the Government of Mozambique reserves the right to choose and provide the land on which to resettle populations and this was the case with the Benga Mine

resettlement.”

According to Tata steel, who holds 35 percent of the shares in the Benga mine, the company “has no executive part in leadership decisions regarding the Benga mine.”

Danwatch has asked Tata Steel if it has taken or plans to take any steps to actively improve the situation in Mualadzi, but the company has not given an answer.

ICVL has been presented with the findings of this investigation but has not responded.

Before Mualadzi was chosen as the new home for the displaced families, community members continuously stressed that year-round water availability was a key conditions for the resettlement site. Worried about the remote location of Mualadzi, they preferred another site closer to their homes in Capanga and Benga Sede near the Revuboè and Zambezi rivers, the Resettlement Action Plan shows.

The plan offers no explanation why Mualadzi was chosen as the most suitable location, other than the fact that it was free of mining concessions.