The steady rise of the skyline over Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, has not yet slowed. Economic growth in one of the world’s poorest countries has accelerated over the last 20 years to more than seven percent annually and today Mozambique is one of the fastest-growing economies in Africa. According to the African Development Bank, the main drivers of growth are FDI and a boom in the extractive industries, propelled by a

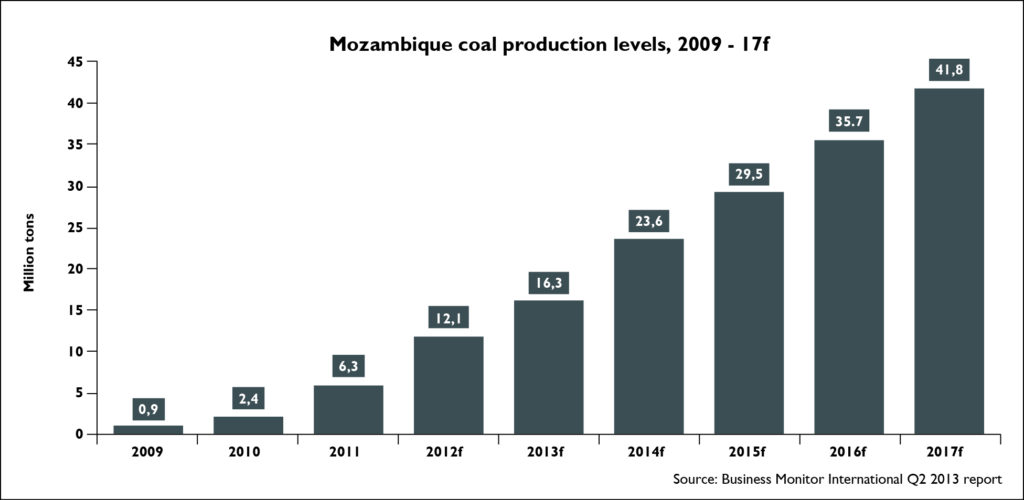

boost in coal exports.

The growing economy is good news for the people who live in the central urban areas of Mozambique, but less so for the poor majority who live in the rural areas. The massive growth has not been accompanied by a decline in the country’s poverty rate, which in 2013 caused UN special rapporteur on human rights and extreme poverty, Magdalena Sepulveda, to raise concerns. She pointed out that Mozambique was about to miss a historic opportunity to use the newfound wealth to alleviate poverty and better the lives for the poorest part of the population.

“There is a risk that those living in poverty in Mozambique will be left behind as the country enters a period of unprecedented economic growth with extractive industries vying to invest in the country’s rich natural resources,” she said, calling on the government to urgently respond to the needs of the poorest and most marginalised in society.

The impressive growth story began with a joint venture in 1998 between the government of Mozambique and BHP Billiton and Mitsubishi Corp in relation to the USD 2.4 billion Mozal Aluminium Smelter Project. The Mozal project was the first major FDI project in Mozambique since the end of the country’s devastating civil war in 1992 and it promised to triple the country’s exports and push growth to previously unseen heights. According to the World Bank, exports from the Mozal Smelter added more than seven percent to the country’s GDP in its initial years.

After the civil war that ravaged the country for two decades, Mozambique adopted an economic development strategy that embraced foreign investment in large-scale mining projects. This marked a new era where a massive boom in FDI contributed in a steep rise to the country’s growth rate. Since 2007, multi-billion dollar investments have been made into mega coal mines and large-scale transport infrastructure.

Mozambique’s subterranean wealth is still attracting a steady flow of foreign investors and mining corporations to the country. Over an eight-year period, FDI grew explosively from approximately USD 122 million in 2005 to over USD 6 billion in 2013, according to World Bank. The size of the extractive sector in Mozambique grew by 22 percent in 2013, largely because of the surge in coal production which, according to African Economic Outlook, increased from 4.8 million ton in 2012 to 7.5 tons in 2013.

Today the map of Mozambique is marked with a vast number of concessions and licences sold to foreign investors. Once a deserted area, the Tete province in central Mozambique has turned into a lucrative centre for extractive industries. As Ben James, managing director of Australian mining house Baobab Resources, recently said to the International Resource Journal:

“By 2025 Tete could be producing 25 percent of the world’s coking coal.”

The ground under Tete is rich with coking coal, which is used worldwide as a vital part of traditional crude steel production. In 2013 African Outlook named the extractive sector one of the fastest growing in Mozambique, largely led by a boost in coal exports. The same year, Mozambique was among the global top ten coking coal exporters with 4 million tons exported, according to numbers from the World Steel Association. The country’s export of coke and semi-coke to the EU market alone was 630,487 tons, according to the ITC Trade Map – a remarkable number given that in previous years there is no registered export to Europe.

The extractive industries is a growing business, according to the latest report from the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative on Mozambique (2012), which is based on the government’s own numbers:

“Extractive industries contributed 2 percent of GDP in 2012. However, investment in the mining and hydrocarbon sectors is growing significantly, promising a rapid expansion of the sectors in the next few years. The oil, gas and mining industry was the fastest growing sector in 2012 and helped propel GDP growth to 7.4 percent. Payments from oil and gas

companies represented 80 percent of the government’s extractive revenue in 2012, while mining companies contributed 20 percent.”

In order for the benefits of a growing resource sector to reach society in general and the poorest people specifically, the extractive industries will have to “contribute to sustainable and broad-based growth,” the World Bank states in its country profile of Mozambique.

“Recent mega-projects in coal, mineral-sands and natural-gas extraction and processing have thus far had only a limited impact on employment and poverty reduction. Some of the challenges ahead include the formulation of strategies for developing Mozambique’s coal and natural gas reserves, determining how these industries interact with other economic sectors, and ensuring that the expected increase in natural resource revenues are used in the most effective way, avoiding the fate of many other natural resource rich countries.”

Despite growth, poverty still prevails, and in some areas it has got even worse. Even though Mozambique has experienced a rise in life expectancy and expected years of schooling, the average Mozambican can expect to live for only 59.4 years, and the quality of education remains too low, according to the UN Human Development Report 2014.

Mozambique is still among the 10 poorest countries in the world, ranking as number 178 out of 187 countries and territories on the UN Human Development Index (HDI). More than half of the population (55 percent) live below the national poverty line and the largest part of the poor population live in rural areas, where they depend on subsistence farming, according to African Economic Outlook 2015. The country’s elite has to secure a more even distribution of the country’s newfound wealth, said UN special rapporteur Magdalena Sepulveda in April 2013.

“It is an unavoidable fact that significant numbers of Mozambicans are living in extreme deprivation and social exclusion. Therefore, those better off in society should strengthen their efforts to ensure everyone can lead a dignified life, a goal that is certainly achievable even within the limited resources of the country.”

In the June 2014 country report presented for the Human Rights Council, the recommendations from the UN special rapporteur to the government of Mozambique were clear:

“As Mozambique enters a period of economic growth, there is a real and tangible opportunity to eradicate extreme poverty, with great potential for future shared prosperity for everyone. The effective implementation of poverty reduction strategies must be considered a matter of priority.”

Political and military tensions in Mozambique escalated in 2014 with violent confrontations between the Renamo opposition and government forces, resulting in civilian deaths, displacement of people and overall disruption of all socio-economic activities. The situation stabilised in September 2014 when the parties signed a peace agreement. The power structure in Mozambique does not allow for any significant change in the country’s distribution policies, says associate professor Lars Buur from Roskilde University and author of The Politics of African Industrial Policy (2015).

“The top leadership, those in charge of the Frelimo Party, make sure that the revenues will continue to benefit the ruling elite.”

According to Lars Buur who has done extensive research into Mozambique’s economic and political landscape, the Frelimo party state has up to 4 million members but is governed by an old post-independence top leadership group of 50 families, among whom 10 families hold the actual power.

“They make sure that all contracts benefit people inside their circle of trust,” he explains.

A high level of corruption and low level of accountability are barriers to development. Mozambique has a score of 30 on the Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), where most corrupt country scores 0 and the least corrupt 100. According to an analysis from Transparency International (2014), patronage and favouritism is a common practice in Mozambique.

“The fact that the executive government concentrates much of the power and is responsible for the appointment of public officials in different government agencies and bodies, makes the reliance on personal and partisan relationships more prominent.”

Favouritism and patronage is not necessarily a problem in itself when it comes to economic growth. The question is how the wealth is distributed, says Lars Buur.

“In Mozambique, distribution is where the real problem lies. In order to control accumulation, the government and the ruling elite will work against economic activities that could actually be very beneficial for the country as a whole because they fear the money could then fall into the hands of opposition. That kind of patronage, corruption or favouritism is very detrimental to economic growth.”

Despite recent efforts to strengthen the country’s tax system by replacing the previous regime with a new mining tax law largely developed by international consultants and experts from the donor community, the reform is unlikely to lead to a more even distribution of wealth in Mozambique, says Buur.

“Despite some weaknesses, the tax laws are of a far better quality than many of the laws we know from Europe. The big issue is how you implement it – to what extent you set up the institutions and give political space for them to work. That is the real battleground,” he says, stressing that laws are worth little without the political will to implement and enforce them.