A 220-metre-long tanker entered the port of Copenhagen on 2 October.

At 18:22, the vessel docked at the oil port at Prøvestenen near Amager and emptied its cargo of around 184,000 barrels of jet fuel, corresponding to almost 30 million litres.

The tanker docked at the large silos of the Danish company Oiltanking Copenhagen on Amager.

This is according to data extracted for Danwatch by the international research institute Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA).

The cargo comes from Vadinar in India and has an estimated value of DKK 150 million based on the price of jet fuel at the time.

On the surface, the jet fuel is Indian, but in reality it is purchased by a Russian-owned company that refines Russian oil and whose ownership structure is designed to just barely evade EU and US sanctions.

The Russian-owned company is Nayara Energy, which controls India’s second largest oil refinery and the associated oil port in the Indian city of Vadinar. Three quarters of the refinery is in Russian hands – the majority directly under the Russian state.

By importing Russian crude oil into India and turning it into jet fuel, they can sell it back to Europe as an Indian product that is not sanctioned.

According to researcher and sanctions expert Kim B. Olsen from the German Council on Foreign Relations, the companies that still buy jet fuel from refineries such as Nayara Energy are undermining the intention of the sanctions aimed at not financing Russia's war in Ukraine.

He is an expert in Europe's use of sanctions and has a career behind him as a foreign affairs analyst at the Danish Institute for International Studies on sanctions.

"It's the European nightmare scenario that you can set up a company in India, buy cheap Russian oil and sell it as jet fuel to Europe, especially when the Russian state is involved," he says.

Although it is legal to buy jet fuel from Nayara Energy, this is only possible because the Russians are exploiting a loophole in the sanctions to continue selling their oil products to Europe. And that's why those who buy these types of products have a great responsibility to carry out a thorough risk assessment of those they do business with, says Kim B. Olsen.

"If a company deals in goods where Russia has traditionally had a large market, such as oil, you should investigate the ownership. Both because of the sanctions, but also to know where the money ends up," he says.

It is easy to see how the 30 million litres of Russian-origin jet fuel ended up in Copenhagen in October. But who ordered and paid for the fuel is still shrouded in mystery.

Danwatch has tried to find an answer.

When the sanctions against Russia were adopted by the EU and the G7 countries, the intention was to stop the invasion of Ukraine by weakening the Russian economy, which is highly dependent on oil exports.

As a result, oil prices were capped and the purchase of a wide range of oil and fuel products from Russia was banned. Consequently, according to Kim B. Olsen, it is contrary to the objectives of the sanctions if Danish companies have found another way to buy the products legally.

"The EU has repeatedly pointed out that it is a problem that Russian oil is shipped to India, refined and sold to Europe. That is not the intention of the sanctions," says Kim B. Olsen.

Danwatch has asked 11 companies at Prøvestenen that either sell, store or use jet fuel whether they have ordered DKK 150 million worth of fuel from the Russian-owned company.

Eight of them flatly deny doing business with Nayara Energy - some even state that they do not import petroleum products from India at all, while one company has not responded to our inquiry.

That leaves SAS and BP, who will neither confirm nor deny whether they have anything to do with the jet fuel.

Oiltanking Copenhagen, which according to CREA received the cargo in Copenhagen, does not want to disclose the identity of the buyer of the jet fuel. CEO Karl Henrik Dahl declines to comment on customer relations, but emphasises that Oiltanking Copenhagen does not import or own fuel itself. They simply own silos at Prøvestenen and offer the storage space to other companies.

However, their customers count some of the largest Danish and international companies, including SAS and BP.

SAS writes in a comment that they have no knowledge of the import of the many litres of jet fuel. SAS does not import fuel to Prøvestenen itself, it says, but has it delivered by BP. However, they will not say whether they have been supplied with jet fuel from Vadinar by BP or whether they have pumped the fuel into their aircraft.

"We cannot comment on who BP has delivered to. That is for BP to do. Unfortunately, we have no further comments beyond the one we have already sent," writes press officer Alexandra Lindgren Kaokji.

According to information collected by Danwatch, it is possible to trace the country of origin of the fuel in Oiltanking Copenhagen's silos. Therefore, in principle, it should be possible for the companies at Prøvestenen to find out whether their jet fuel has come from India or not, regardless of who the supplier may be.

The British BP press office will not comment on the 30 million litres of jet fuel, but confirms that they deal with refineries like the one Russia controls in Vadinar. However, BP will neither confirm nor deny whether they are behind the shipment in question.

"BP purchases refined products worldwide, including from such refineries, in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations," the company writes in an email.

It is therefore not possible for Danwatch to get a concrete answer to this essential question:

Who will own up to buying Russian jet fuel for DKK 150 million?

The sanctions on Russia's oil exports were imposed to minimise the country's profits from their production of oil and oil products. The intention was not to stop the export, but to make sure Russia couldn't make too much profit from it.

That's why they put a price cap on the products. But Russia has earned over DKK 75 billion more than what the sanctions allow, according to an analysis by Bloomberg.

According to Kim B. Olsen, this possibility leads to several questions about the effect of the sanctions.

"It's a really good example of how quickly you can end up financing the Russian war machine. People keep buying Russian products, even though that may not be what they were expecting," he says.

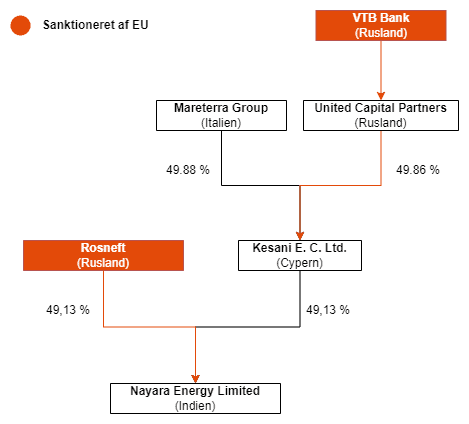

About half of Nayara Energy is owned by the Russian state through the oil company Rosneft and about 25 per cent by a private equity fund founded by a Russian billionaire and oligarch connected to Rosneft.

There is a lack of "light in the room", says Kim B. Olsen, whose European companies on the one hand take a stand in favour of Ukraine, but on the other hand help finance the war by buying fuel from a Russian-owned refinery.

"There is no transparency. Even if it's legal, the question is whether it's morally right. It's ultimately up to the consumer. Therefore transparency is important," says Kim B. Olsen.

Among other things, SAS has previously condemned the Russian war in Ukraine and even removed products from Mondelez and PepsiCo from its aircraft because they are accused by Ukraine of sponsoring Russia's invasion.

Data from CREA shows that approximately half of all oil imported by Nayara Energy comes from Russia.

On MarineTraffic, Danwatch has followed several vessels sailing to and from the oil port in Vadinar. We have compared them with data from Lloyd's List Intelligence, an international maritime data company, on the Russian dark fleet, which is used to circumvent the sanctions.

This shows that the dark fleet is a major supplier of oil to Nayara Energy's port facility in Vadinar.

Experts from Lloyd's List Intelligence and the World Bank believe that the dark fleet is one of the main reasons why Russia is able to circumvent Western sanctions on Russian oil exports. Among other things, the World Bank has called the price cap almost impossible to enforce.

Large portions of the refinery's crude oil for the production of jet fuel are most likely overpriced and are therefore banned under US and EU sanctions.

The consequence is that Russia can sell its oil at a much higher price. The sanctions have capped the price of Russian crude oil at $60 per barrel, yet the average price of Russian crude oil is often much higher because the price cap is not respected.

In this way, Russia earns more money for the treasury and thus for the financing of the very war in Ukraine that caused the sanctions to be adopted in the first place.

There are also examples of supplies to Vadinar from companies that, according to US authorities, are in violation of the sanctions.

For example, the tanker NS Consul, which passed Skagen on Monday 27 November on its way to India and Vadinar. It is owned by the shipping company Oil Tankers SCF Management in Dubai. SCF in this context stands for Sovcomflot, Russia's state-owned shipping company.

Several vessels from Oil Tankers SCF were in November accused by US authorities of trading in sanctioned oil, according to Reuters.

It only makes the case more serious that Nayara Energy's suppliers are accused of sanctions violations, says Kim B. Olsen.

"It certainly challenges the intent of the sanctions significantly. There are always loopholes in sanctions due to complex markets and difficult legal issues, but when they are exploited like this, you undermine the purpose of the sanctions," he says.

We are still left without an answer to the question of who bought around DKK 150 million worth of jet fuel from a company controlled by Russia. A purchase for which no one has been willing to take responsibility.

In 2016, India's Nayara Energy was sold to a group of foreign investors. According to Reuters, the deal was the largest foreign acquisition in India to date and the largest investment Russia had ever made abroad.

Both Vladimir Putin and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi were present when the agreement was finally signed in October 2016.

The sale was carefully structured so that Rosneft's ownership of Nayara would not exceed the 50 per cent that would otherwise subject Nayara to Western sanctions.

The remaining shares were instead acquired by a consortium of Russian and European investors under the Cyprus-based holding company Kesani Enterprises Company Limited.

This ownership structure makes sense given Russia's strategy of not being cowed by Western sanctions. A strategy that began after the Russian annexation of the Ukrainian Crimean peninsula almost a decade ago.

"Since 2014, Russia has done a lot of preparation to be able to circumvent and counteract Western sanctions. The fact that it's in the statutes just emphasises the reason why they do it," says Kim B. Olsen.

The Russian state was also deeply involved in the acquisition of the holding company.

Because according to a 2021 notification to the Indian stock exchange authorities, the money for the share of the Kesani consortium came from a huge loan from the Russian state-owned VTB Bank, which, like Rosneft, is subject to sanctions in both the EU and the US.

As collateral for the loan of up to DKK 25 billion, the consortium has pledged all its shares in Nayara Energy.

One of the main investors in Kesani is Russian oligarch and billionaire Ilya Sherbovich, who through his investment company United Capital Partners owns approximately 25 per cent of Nayara.

With a background as a board member of several of Russia's largest banks and oil companies - including Rosneft - Sherbovich has long been close to the Russian political elite.

While he himself is not sanctioned by either the US or the EU, he is identified by the Ukrainian authorities as a close friend of the Kremlin, personally coordinating all major transactions with a member of Putin's inner circle, Igor Sechin, who is currently the head of Rosneft.

Sherbovich himself has previously said that he is in regular contact with Sechin - albeit not as often as before - in connection with their joint projects. He also personally holds shares in Rosneft.

According to the ownership agreement, Rosneft, and thus the Russian state, has the right of first refusal to bid for the supply of crude oil to Nayara's refinery at Vadinar. And should Nayara receive a better offer, Rosneft has the right to match the price, after which Nayara is obliged to enter into a contract with Rosneft.

While it is still legal to do business with Nayara Energy despite the ownership structure, companies should realise that this is also because it may be too complicated to do so illegally.

Countries such as India have a completely different perspective on the war in Ukraine, and therefore Russia can hide behind the fact that the Indians are a Western partner that does not follow Western sanctions, says Kim B. Olsen.

"This is a political dilemma. It could just as easily be an attempt to put pressure on the Indians. But the pressure is limited when sanctions are circumvented in economically powerful countries with which the West would like to have a good relationship," he says.